This is my MHS graduate manuscript titled, “A Narrative Review: The Effects of Intuitive Eating on Body Image, Health Practices, and Life Quality in Females” by Rachel L. Beiler, RD, LDN

Table of Contents

Abstract

Background: Today, the focus of health is achieving weight loss. Weight loss is traditionally achieved by decreasing overall caloric intake from food while simultaneously increasing the number of calories burnt from physical activity. This method is commonly used because individuals often associate a decrease in weight with an increase in health. With this heavy emphasis on weight loss in today’s society, the prevalence of body image dissatisfaction is at an all-time high, especially among females. This can lead to disordered eating habits, poor healthy living practices, and an overall low quality of life. However, research is demonstrating that weight loss is not a long-term or effective way to achieve overall health. Instead of weight loss, research is supporting a focus on determining health based on an individual’s overall feeling of wellbeing, biochemical data, and mental health. This switch emphasizes healthy living practices such as eating a healthful, balanced diet, participating in physical activity, and improving mental health. Research is showing that non-diet approaches to health, such as Intuitive Eating (IE) and Health at Every Size (HAES), are better options than weight loss. These approaches focus on nourishing an individual’s physical and mental health without pursuing restrictive, harmful habits.

Objective: To carry out a narrative review of the effect of Intuitive Eating on body image acceptance, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life in females 13 years and older.

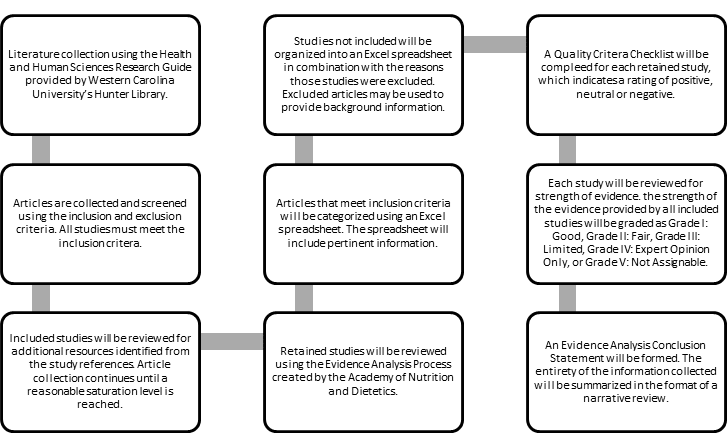

Method: A narrative review will be performed. A search of the literature from 2009 to the present will be done utilizing the Health and Human Sciences Research Guide provided by Western Carolina University in order to identify peer-reviewed articles that discuss the effect of Intuitive Eating on females 13 years and older. Articles will be reviewed using the Evidence Analysis Process created by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics. Information received from the reviewed articles will be compiled and reported in the format of a narrative review.

Anticipated Results: The study results are anticipated to show that Intuitive Eating has an overall positive effect on body image acceptance, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life in females 13 years and older.

Anticipated Conclusion: Intuitive Eating helps to improve body image acceptance, healthy living practices, and quality of life in females 13 years and older.

Chapter 1. Introduction

Overview of Dieting Trends

Over recent years, dieting has taken over the health and wellness world (Harrison, 2018). Hundreds of diets have been created by doctors, nurses, nutritionists, dietitians, and other health professionals. These diets promise a healthier body and life through successful weight loss (Harrison, 2018). The popularity of dieting has grown to the point that the majority of people have dieted several times throughout their lifetime. Within the dieting community, it is commonly thought that an individual is not considered healthy unless the individual is on a diet and pursuing weight loss (Harrison, 2017).

Commonly known diets include the Atkins Diet, which has been rebranded as the Ketogenic Diet. This diet emphasizes low-carbohydrate intake while simultaneously increasing fat and protein intake in order to lose body fat (Harrison, 2018). Another popular diet is Paleo, which encourages eating only foods that could theoretically be scavenged or hunted such as meat, berries, seeds, and nuts (Harrison, 2018). Other well-known diets include meal plans such as Weight Watchers, Jenny Craig, or Nutrisystem which involve calorie counting, support groups, and meal delivery services. The list of popular diets is almost never ending and includes diets such as the Alkaline Diet, Whole30, detox diets, juicing, Raw Food Diet, Blood Type Diet, Zone Diet, Macrobiotic Diet, Grape Fruit Diet, gluten free diet, etc (Harrison, 2018).

One thing all diets have in common is a goal of weight loss in order to improve health and enhance physical appearance (Harrison, 2017). However, although diets promise weight loss, current research is showing that no diet or combination of diets has been able to prove that the achieved weight loss is sustainable. Research is showing that, as time passes, diets are incapable of maintaining the achieved weight loss (Harrison, 2017).

Shifting the Focus of Health

After years of the health and wellness industry being dominated by diets, research began to emerge that discussed the dangers of dieting. Research started demonstrating that dieting leads to decreased metabolism, weight re-gain, obsession with food, low self-esteem, eating disorders, and more (Harrison, Zavodni, 2019). In addition to this, research also started demonstrating that health cannot be accurately determined by weight. The Health at Every Size (HAES) movement, founded by health professionals, started to argue and prove that weight is not a determinant of health. HAES demonstrated that health can be achieved at any body weight, thus decreasing the need for diets and weight loss (ASDAH, 2013).

As new research continued to be published and support the omission of diets, certain health professionals started to shift the focus of health from weight loss to overall well-being. This shift emphasized eating a balanced diet, participating in enjoyable physical activity, and basing health on how an individual feels, not how an individual looks (ASDAH, 2013). Health professionals began to leave weight-centered health promotion and instead began to emphasize weight-neutral health promotion. During this shift and research period, two registered dietitians created Intuitive Eating, a non-diet approach to health that emphasizes a healthy relationship with food and an individual’s body. During recent years, Intuitive Eating has gained popularity in the health and wellness world and has begun to revolutionize what health really is (Tribole, Resch, 2012).

Introduction to Intuitive Eating

Created by two registered dietitians, Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch, Intuitive Eating (IE) is an evidence-based, mind-body health approach that is comprised of 10 core principles. Intuitive Eating is a personal process of honoring health by listening and responding to the direct messages of one’s body in order to meet one’s physical and psychological needs. Intuitive Eating is not a diet or food plan. The goal of IE is not weight loss; instead the goal is to create a healthy relationship with food, physical activity, and personal body image (Tribole, Resch, 2012).

Operational Definitions

Registered Dietitian (RD): A food and nutrition expert who has completed a bachelor’s degree from a program approved by the Accreditation Council for Education in Nutrition and Dietetics (ACEND), completed an ACEND accredited dietetic internship program, successfully passed the national RD exam provided by the Commission on Dietetic Registration (CDR), and continues to complete required continuing professional education requirements (AND, 2013).

Intuitive Eating: An evidenced based, mind-body health approach, comprised of 10 principles and created by two dietitians, Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch (Tribole, Resch, 2012).

Health at Every Size (HAES): Created by the Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH); an approach to health that affirms a holistic definition of health, which cannot be characterized by the absence of physical or mental illness, limitation or disease, instead health exists on a continuum that varies with time and circumstance for each individual; involves 5 main principles – weight inclusivity, health enhancement, respectful care, eating for well-being, and life-enhancing movement (ASDAH, 2013).

Eating disorder: Serious and sometimes fatal illnesses associated with severe disturbances in people’s eating behaviors and related thoughts and emotions; characterized by preoccupation with food, body weight, and shape; common eating disorders include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder (NIH, 2016).

Body image: How one sees oneself when looking in the mirror or when picturing oneself in one’s mind; encompasses what one believes about one’s own appearance, how one feels about one’s body, and how one senses and controls one’s body (NEDA, 2018).

Health practices: Diet patterns, physical activity levels, and mental health status

Life quality: The standard of health, comfort, and happiness experienced by an individual or group

Problem Statement

The purpose of this research project is to determine the effect of Intuitive Eating on the general health practices, body image satisfaction, and overall life quality of females ages 13 years and older. Research shows that females experience the negative impacts of dieting the most in comparison to males (Harrison, 2017). Through this research, a potential solution could be found that links Intuitive Eating to increased health practices, body image satisfaction, and life quality in the population of interest.

Chapter 2. Literature Review

Overview

Today, the overarching focus of health is to successfully achieve weight loss. This is typically accomplished by decreasing calorie intake from food while increasing calories burnt from physical activity. This is because it is commonly thought that a decrease in weight is synonymous with an increase in health. However, current research is showing that weight loss is not a sustainable or effective way to achieve overall health. Instead, certain health practitioners have proposed the idea of shifting from emphasizing weight loss to focusing on an individual’s overall health based on feeling and biochemical health data (Harrison, 2017). This shift of focus puts an emphasis on healthy living practices such as eating a balanced diet, participating in physical activity, and improving mental health (Harrison, 2017). By doing this, weight is no longer being used as an identifiable factor for health. Due to this progression in the thought behind what health really is, movements such as Intuitive Eating, Health at Every Size (HAES), and the Anti-Diet Movement have been created. These movements focus on nourishing the mental and physical body through food and enjoyable physical activity with no regard to weight (Harrison, 2018). Intuitive Eating abandons the idea of focusing on weight loss through restrictive habits that can result in metabolic damage to the body.

The concept of Intuitive Eating can be used to help individuals heal one’s relationship with food and body. In theory, Intuitive Eating can help improve psychological health by potentially improving self-esteem, body image dissatisfaction, overall quality of life, and restrictive eating habits. It can also, in theory, enhance physical health by potentially improving participation in physical activity, types of foods eaten, relationship with food, restrictive food habits, binge eating, undereating, and disordered eating patterns. However, despite the possible benefits of Intuitive Eating, not all health professionals are in agreeance with the usage of Intuitive Eating. The main drawback of Intuitive Eating is the possibility of it not only leading to the inability to lose weight, but it increasing the chances of weight gain, since food is not restricted (Anglin, Borchardt, 2015). This drawback results in a constant debate between health professionals who follow a weight-neutral approach to health and those who follow a weight-centered approach to health.

Basis for Methodology

The chosen methodology for this study is a comprehensive narrative review. The key words and phrases include: Intuitive Eating, influence of Intuitive Eating, effect of Intuitive Eating, influence of Intuitive Eating on females, effect of Intuitive Eating on females, and results of Intuitive Eating. These terms were used to ensure a broad overview of Intuitive Eating and its influence on individuals. Additional terms that could have also been used during this search process include body image, quality of life, and health practices. However, these terms were not used during the research process in order to keep the search broad and prevent valuable research articles from not being discovered. Once this process was complete, the resources identified were also searched for additional valuable resources.

Intuitive Eating

Intuitive Eating (IE) is a program created by two registered dietitians, Evelyn Tribole and Elyse Resch. (Tribole, Resch, 2012). These dietitians specialize in eating disorders and are passionate about helping people develop a healthy relationship with food and body. Intuitive Eating is an evidence based, mind-body approach to health that uses a non-diet and weight-neutral model. It is important to know that Intuitive Eating is not a diet. Instead, it is a non-restrictive program that helps one connect with the body’s needs and become the expert of self. It was created to be a tool of empowerment to help free people from weight obsession and diet culture. Today, diet culture can be defined as a community that praises the idea of the “ideal body,” which is small and provides an individual with additional value to society. Diet culture encourages food restriction, excessive exercise, and uses weight as the primary indicator of health. The goal of Intuitive Eating is to leave dieting, food restriction, body dissatisfaction, and weight stigma behind to pursue overall health and wellness.

To adopt Intuitive Eating into a daily routine, there are 10 principles to help guide individuals through the process. 1. Reject the Diet Mentality. This means to forget and stand up to the lies diet culture teaches. This involves no longer participating in fad diets, calorie counting, over-exercising, or restrictive behaviors. 2. Honor Your Hunger. This principle focuses on the importance of receiving proper nourishment through consuming an adequate balance of macro- and micro-nutrients. This also involves learning to listen to and act accordingly to physical hunger. 3. Make Peace with Food. This principle reinforces one of the most importance practices in Intuitive Eating, giving oneself unconditional permission to eat. This is important because restricting or depriving oneself of certain foods can lead to an unhealthy relationship with those foods. 4. Challenge the Food Police. The Food Police are the people and an individual’s internal thoughts that monitor rules around food consumption. This principle involves the “re-wiring” of the brain to not label foods as “good” or “bad.” 5. Respect Your Fullness. This principle involves learning how to identify when one’s body feels comfortably full. This is not meant to be a restrictive behavior but it is meant to help one listen to the body and prevent overeating, which can often lead to guilt and compensatory behaviors. 6. Discover the Satisfaction Factor. This principle focuses on eating what the body desires, in an inviting and peaceful environment, to help the body feel satisfied and content, thus, leading to a healthier relationship with food and body. 7. Honor Your Feelings Without Using Food. Intuitive Eating focuses on finding ways to cope with life that do not involve food. By practicing this, food is no longer seen as a tool to drown emotions but as a positive experience used to nourish the body. This also helps one to develop proper coping strategies to stress, sadness, anger, and other emotions. 8. Respect Your Body. Intuitive Eating focuses on the fact that bodies come in all shapes, size, and colors. An individual’s health cannot be determined by external appearance and it is important to learn to respect the body. 9. Exercise – Feel the Difference. The focus of this principle is to develop a healthy relationship with physical activity by participating in enjoyable exercise and moving in ways that feel good to an individual’s body. 10. Honor Your Health. Intuitive Eating focuses on choosing foods both that honor health and the body’s taste buds. An individual should choose foods that make one feel physically and mentally healthy (Tribole, Resch, 2012).

In comparison, as a whole, the principles of Intuitive Eating contrast and challenge traditional strategies of achieving health. Traditional strategies encourage calorie counting, restricting certain foods and/or food groups, fasting for extended periods of time, setting weight loss goals, achieving a certain physique as well as additional strategies. On the other hand, Intuitive Eating focuses on honoring hunger and satiety cues while making peace with food instead of restricting intake. Intuitive Eating focuses on respecting the body instead of striving for weight loss and a particular physique or body type (Tribole, Resch, 2012).

Intuitive Eating and the General Population

Several studies were reviewed that involved collecting data on a population and correlating that data to the degree of Intuitive Eating experienced. These studies involved female participants that varied in age and the use of various measurement tools to determine degree of Intuitive Eating as well as its impact. (Andrew, Clark, 2016, Augustus-Horvath, Tylka, 2011, Schoenefeld, Webb, 2013)

A longitudinal study by Andrew and Clark investigated prospective predictors and health-related outcomes of positive body image in adolescent females (Andrew, Clark, 2016). The participants were a subset of a larger cross-sectional study investigating a model of Intuitive Eating. The participants completed two separate questionnaires that included measures of activity, media consumption, body appreciation, self-objectification, social appearance comparison, perceived body acceptance, health behaviors, and general demographics. Participants were also asked about intuitive eating habits and patterns. The data was then analyzed to determine the link between an individual’s level of intuitive eating and its impact on body appreciation, quality of life, and other topics addressed. The results suggested that enhancing body appreciation might be one way to tackle the development of disordered eating that is highly prevalent amongst adolescent females. The results also showed that public health programs for adolescents that focus on weight may negatively impact body appreciation while more holistic programs, such as Intuitive Eating, that challenge weight stigma, encourage body acceptance, and focus on an overall healthy lifestyle are likely to be more beneficial for both physical and psychological health.

A similar study by August Horvath and Tylka involved women of varying ages (emerging adulthood, early adulthood, and middle adulthood). The participants completed various surveys that assessed support systems, body acceptance, perception of body shape/size, overall life satisfaction, and level of intuitive eating. The degree of intuitive eating was compared to the participants’ body image satisfaction, overall quality of life, and other topics addressed. The results indicated that an increase in perceived social support was associated with body acceptance of others as well as an increase in body appreciation and intuitive eating when others approved of their bodies.The authors concluded that the higher the degree of intuitive eating, the more likely a participant was to have a positive body image as well as an increased level of life satisfaction.

A third study by Scheonegeld and Webb involved female undergraduate students that completed various online surveys including the Self-compassion Scale (SCS), the Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS), the Body Image Acceptance and Action Questionnaire (BI-AAQ), the Intuitive Eating Scale (IES), and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSES). The results of the surveys indicated that participants that scored high on self-compassion reported higher levels of intuitive eating, distress tolerance, and body image flexibility. The results also showed that participants that reported higher levels of intuitive eating tended to report high levels of body image acceptance. These results strongly suggest that practicing the principles of Intuitive Eating can lead to increased body image satisfaction and improved self-esteem/self-love.

In summary, these research studies demonstrated that Intuitive Eating can increase the likelihood of a participants experiencing a positive body image as well as increased self-love and acceptance. In addition to this, the studies demonstrated that Intuitive Eating can positively influence an individual’s overall healthy lifestyle and can result in an increased life quality.

Intuitive Eating Integrated or Combined with Health Programs

Several studies were reviewed that involved the integration or combination of Intuitive Eating and existing health programs. These studies involved predominantly female participants that completed health programs or health interventions that were combined with Intuitive Eating practices (Bush, Rossy, 2014, Cole, Horcek, 2010, Loughran, Harfel, 2018, Cadena-Schlam, Lopez- Guimera, 2015).

An experimental study by Bush and Rossy determined the difference between two groups of females. The intervention group participated in the Eat for Life class (combination of Intuitive Eating and mindfulness approaches) while the control group did not. The results showed that the intervention group reported higher levels of body appreciation and lower levels of problematic eating behaviors in comparison to the control group. The results demonstrated that the intervention group experienced an overall increase in life satisfaction and body acceptance while practicing the principles of Intuitive Eating.

A similar experimental study by Cole and Horcek involved the intervention group participating in the My Body Knows When Intuitive Eating program while the control group did not. After the completion of the My Body Knows When program, the results showed that the intervention group displayed signs of rejecting the “diet-mentality”, improved self-worth, and reduction in emotional eating. The intervention group showed signs of increased body acceptance and improvements in overall healthy eating practices.

An additional experimental study by Loughran and Harfel observed the effect of an Intuitive Eating text-message intervention on college students. The study involved ten text messages (2 texts/week) regarding Intuitive Eating reminders. The results showed a positive correlation between Intuitive Eating and self-efficacy, new found food independence, increase in desire for healthy behaviors, and decreased levels of perceived stress. The results suggested that those who were reminded to practice the Intuitive Eating principles experienced an overall improvement in body image satisfaction and healthy living practices.

In addition to these experimental studies, a review study conducted by Cadena-Schlam and Lopez- Guimera selected eight different research articles that aimed to explore the effectiveness of interventions based on Intuitive Eating and the Health at Every Size (HAES) principles. The results of the review showed that using Intuitive Eating alone or in conjunction with another program, such as HAES, may be a more promising and realistic method to addressing overweight and obesity than conventional weight-loss treatments. It demonstrated that Intuitive Eating can help meet an individual’s health goals and does not negatively affect the integrity and welfare of the patient. It found that Intuitive Eating protects people of all sizes from unhealthy weight-focused behaviors that may diminish an individual’s overall health and well-being.

In summary, these studies demonstrated that wholistic approaches to health, such as Intuitive Eating can positively influence body image and increase body acceptance. In addition to this, Intuitive Eating can help decrease problematic eating habits and reduce the level of emotional eating. These studies demonstrated that Intuitive Eating can meet health goals and improve the welfare of participants by healing participant’s relationship with food as well as their outlook on weight-focused behaviors.

Intuitive Eating in Specialized Fields of Study

Two specialized Intuitive Eating studies were discovered during the literature search. These studies focus on two groups of females that are at an increased likelihood of disturbed body image and disordered eating habits (Plateau, Petrie, Papathomas, 2017, Richards, Crowton, Berrett, 2017).

One study by Platueau, Petrie, and Papathomas involved retired collegiate female athletes. This is a specialized study because female athletes are known to have an increased likelihood of disordered eating patterns and body image dissatisfaction. The participants completed various surveys that inquired about their level of intuitive eating and the results of incorporating Intuitive Eating into daily life. The participants also answered questions regarding how their health habits changed after retirement from their sport. The study showed that most of the participants reported that their frequency and/or quantity of eating changed after retirement. (Plateau, Petrie, Papathomas, 2017).

Many of the participants resonated with questions regarding Intuitive Eating principles including permission to eat, recognizing internal hunger and satiety signals, and eating to meet physical and nutritional needs. This was because many of the athletes experienced constraints around food intake while competing. These constraints included avoidance of “unhealthy” foods, limited caloric intake, rigid eating schedules, loss of hunger and satiety cues, and negative emotions around food. The results of the surveys showed that Intuitive Eating principles can help retired female athletes resume a “normal” pattern of eating and reduce disordered eating practices. The results also found that Intuitive Eating can be effectively used to improve the participant’s body acceptance and general healthy living practices. However, it was noted additional research is needed to understand the process of helping retired female athletes develop a healthier approach to eating.(Plateau, Petrie, Papathomas, 2017).

The second specialized study by Richards, Crowton, and Berrett, involved women at an inpatient-residential care facility for females with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating, eating disorder-not other specified, and additional comorbid diagnoses. (Richards, Crowton, Berrett, 2017). The participants received education on the ten Intuitive Eating principles and registered dietitians met with the patients individually each week in order to discuss Intuitive Eating. Via observation of the patients during admission in the inpatient-residential care facility, the results showed that the participants developed healthier attitudes towards food/eating and learned to apply the principles to make healthier choices. The results also showed a reduction in depression, anxiety, and conflicts with body image. The authors inferred that Intuitive Eating can be an effective intervention when working with eating disorder patients (Richards, Crowton, Berrett, 2017).

In summary, these specialized studies show that Intuitive Eating can have an overall positive impact on individuals at increased risk of negative body image and disordered eating practices. These studies demonstrated that Intuitive Eating can help individuals develop a healthy approach to eating and make peace with food as a whole. In addition to this, these studies demonstrated that Intuitive Eating can positively influence body image and acceptance, even in individuals that have developed eating disorders.

Research Focus

The focus of this research is to identify robust, peer reviewed studies that discuss the relationship between Intuitive Eating and its impact on a female’s body image satisfaction, health habits, and quality of life. The goal of this narrative review is to answer a proposed research question: What is the effect of Intuitive Eating on body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life in females ages 13 and older?

Chapter 3. Methodology

Research Design

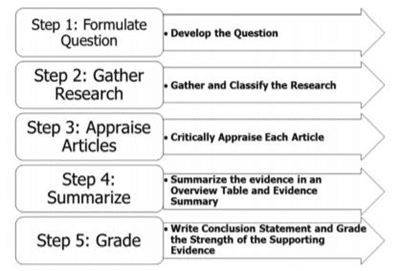

A comprehensive narrative review will be conducted to review the effect of Intuitive Eating on body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life among females 13 years of age and older. The review will be done according to the Evidence Analysis Process created by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND). There are few studies that evaluate and summarize the current research available on the topic of Intuitive Eating. Completing a narrative review will help form a broad perspective of the topic of interest and will provide a comprehensive and critical analysis of the current knowledge of this topic.

Data

Setting:

The literature reviewed for this study will include articles in English. The research will not be limited to specific settings since Intuitive Eating can occur in every aspect and setting of life. In the end, observing the impact of Intuitive Eating on females 13 years and older within various life settings will allow an understanding of the relationship between Intuitive Eating, body image, health practices, and quality of life to be developed.

Population:

Information regarding this population will be collected through the Health and Human Sciences Research Guide provided by Western Carolina University’s Hunter Library. This database includes but is not limited to Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied health (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, Medline, Psyctests, Psycinfo, and Socindex.

Sample:

The population of interest is females ages 13 and older. This is because the prevalence of body image dissatisfaction, which can lead to disordered eating patterns, poor healthy living practices, and an overall low quality of life, is the highest among females. It is more common for females to be unsatisfied with their exterior appearance than it is for males. This dissatisfaction often leads to compensatory behaviors that influence diet patterns and mental health status (Eating Disorder Hope Organization, 2020). It is crucial to investigate females of all ages because this problem occurs during various stages in life or throughout an individual’s entire lifespan. In order to provide a summary of how females are influenced throughout life, the age criteria will be greater than or equal to 13 years of age. Choosing to look at research starting at 13 years old is important because that age signifies the becoming of a teenager, which is a critical time for physical and mental development within women.

Search phrases used to define the sample include Intuitive Eating, influence of Intuitive Eating, effect of Intuitive Eating on females, influence of Intuitive Eating on females, and results of Intuitive Eating.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria:

Studies will be screened using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. All retained studies must meet inclusion criteria.

Inclusion:

- Published between January 2009 – Present

- English language or articles published in English

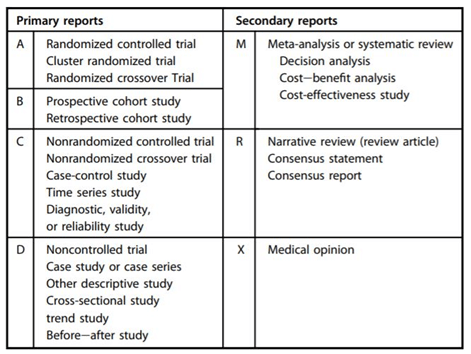

- Randomized control trials, meta-analyses, narrative review and other forms of literature reviews, cohort study, cross-over study, descriptive study, cross-sectional study, longitudinal study

- Full-text articles

- Peer reviewed articles

- Gender specific data separate for ease of analysis of female participants

- All races/ethnicities

- Participant age range: >13

- Contains at least 1 of 3 dependent variables (body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and quality of life)

- Size of study groups >30 participants

- Study dropout rate <20%

Exclusion:

- Published before January 2009

- Published in a language other than English

- One-shot case studies, before-after study, cost benefit analysis, diagnostic/validity/reliability study, intention to treat analysis, magnitude of effect, non-controlled trial, non-randomized controlled trial, phenomena, time series, trial, trend study

- Articles that are not full-text

- Articles that are not peer reviewed

- Articles researching the correlation between IE and weight loss

- Gender data aggregate only

- No race/ethnicity exclusions

- Participants age range: <13

- Does not contain at least 1 of 3 dependent variables (body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and quality of life)

- Size of study groups <30 participants

- Study dropout rate >20%

Variables

Independent Variable(s):

The independent variable for this study includes the presence of/participation in Intuitive Eating. A nominal variable categorized as “yes” or “no.”

Dependent Variables:

The dependent variables for this study include the level of body image satisfaction, healthy living practices such as diet patterns as well as physical activity habits, and overall quality of life of the participants. Variables will be measured based on the information provided by studies that are reviewed.

Demographic Variables:

The demographic variable for this study includes females 13 years and older. Level of measurement will be years and the study participants will be categorized by age.

Instrumentation

Data Collection Instruments:

A comprehensive Excel spreadsheet will be used to organize, summarize, and characterize studies selected, how obtained and the disposition of those articles. A detailed flow chart will be used to graphically display the research and data collection process.

Administrators:

The study administrator will be Rachel Beiler, author, with assistance from a graduate faculty mentor.

Procedures:

In order to evaluate the effect of Intuitive Eating on body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life among females 13 years and older, a series of steps will be taken. The review process will follow the guidance of the Evidence Analysis Process created by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND), which is described in detail below. First, literature will be collected by using the Health and Human Sciences Research Guide provided by Western Carolina University’s Hunter Library. This database includes but is not limited to Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied health (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, Medline, Psyctests, Pstcinfo, and Socindex. Examples of key words and phrases used will include: (“Intuitive Eating” or “IE”) and (“influence of Intuitive Eating” or “results of Intuitive Eating”) and (“effect of Intuitive Eating on females” or “influence of Intuitive Eating on females)

Second, the articles collected will be screened initially using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All studies must meet the criteria. Studies that satisfy the criteria, will be reviewed for additional resources identified from the study references. This process will continue until a reasonable saturation level is reached. Studies that do not satisfy the criteria, will be organized in an Excel spreadsheet in combination with the reasons those studies were excluded (See Table 5 in Appendix B). These discarded articles may be used to provide background information regarding Intuitive Eating, as needed.

Third, articles that meet the inclusion criteria will be categorized using an Excel spreadsheet. A summary of pertinent information discovered through the included articles will also be organized using an Excel spreadsheet. In addition to this, a flowchart will be created that identifies how and what articles made it through the inclusion/exclusion process.

Errors and Limitations

Due to the nature of narrative reviews, there is an increased chance of bias as well as the exclusion of certain literature, since the methods used to obtain literature cannot ensure that all literature is considered. In addition to this, upon searching the current literature, it appears that limited data is available on this subject.

Potential Bias

No potential bias has been identified among the research articles reviewed thus far. The study administrator, Rachel Beiler, has chosen to set any personal biases aside during the proposal and research periods.

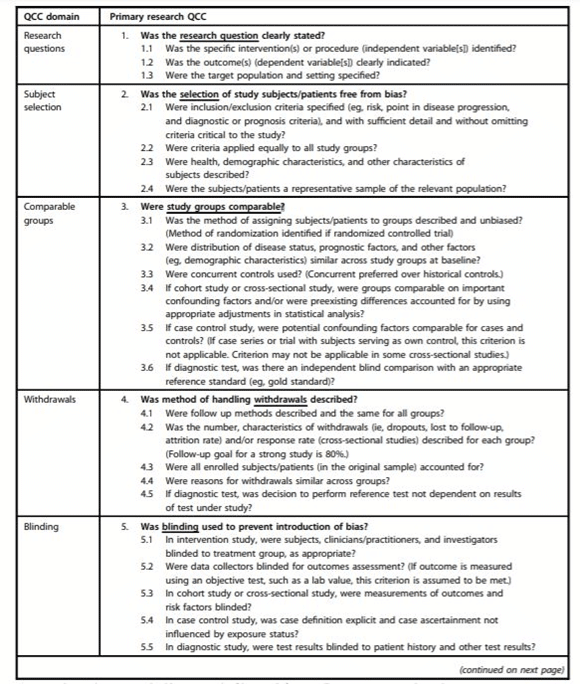

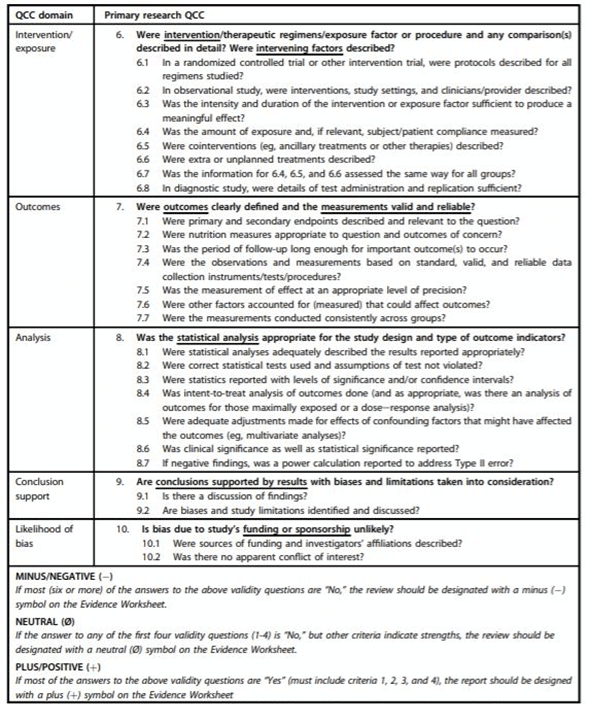

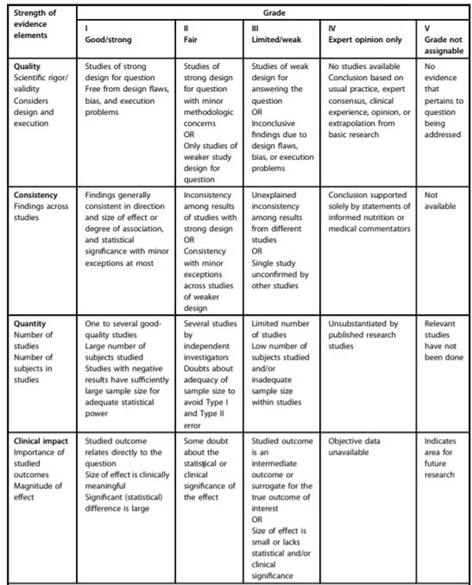

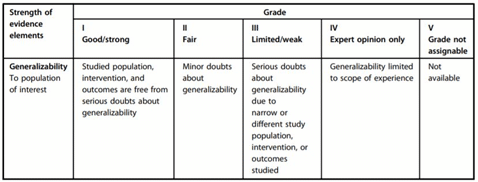

Analysis of Findings

The retained studies will be read thoroughly and reviewed. Various information from the studies will be recorded in a comprehensive Excel spreadsheet. The Evidence Analysis Process created by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND) will be used to review and rate each study as well as grade the overall evidence provided. This process is done by completing a Quality Criteria Checklist (QCC) for each retained study reviewed, which indicates the rating of the study as positive, neutral, or negative. After each study has been reviewed using the Quality Criteria Checklist, the strength of the evidence provided by all included studies will be graded as Grade I: Good, Grade II: Fair, Grade III: Limited, Grade IV: Expert Opinion Only, or Grade V: Not Assignable. Once all studies have been thoroughly examined and the Evidence Analysis Process is complete, the information collected will be summarized in the format of a narrative review. See Appendix C for more information regarding the Evidence Analysis Process.

Chapter 4. Results

The Evidence Analysis Process – A Five Step Process

The Evidence Analysis Process was created by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics (AND). The process is used to review literature regarding a topic of interest. During the process, scientific articles are reviewed according to a search plan defined by the researcher. Next, the articles are graded for quality of research and the information provided in the included articles is summarized. Last, the current research regarding the topic and research question of interest is given a grade to dictate the overall quality of the articles as well as the conclusions that were drawn. Further information regarding the Evidence Analysis Process can be found in Appendix C.

Step 1 – Formulate the PICO Question

To begin, a PICO question was formed according to the Evidence Analysis Process guidelines. PICO stands for: Population (patient or problem), Intervention (cause, treatment, or prognostic factor), Comparison intervention (if necessary), and Outcomes. For this narrative review, the population was decided to be females ages 13 years and older; the intervention was practicing Intuitive Eating; the comparison was not practicing Intuitive Eating; and the outcomes were body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and quality of life. This results in a PICO question: What is the effect of Intuitive Eating on body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life in females ages 13 years and older? It is important to note that the comparison (the C in PICO) is not included in the PICO question in order to fulfill the graduate level research question requirements. The PICO question was approved by the MHS program director. See Table 1 in Appendix B for the completed table used by AND to create the PICO question.

Step 2 – Gather & Classify Research (Develop Search Plan)

The search plan developed according to the Evidence Analysis Process was used to determine the search terms/phrases, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, and electronic databases. This information was discussed in details in Chapter 3. By using the search terms and inclusion/exclusion criteria, a total of 50 research articles were collected. Of the articles collected, 16 articles met the inclusion criteria and 34 did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the 16 articles included, 13 were primary research and 3 were secondary research. The list of excluded articles and reasons for exclusion can be found in Appendix B. The main reasons articles were excluded were irrelevancy to research topic, lack of discussion of IE, participants <13 years old, articles not written in English, and results not sorted according to sex. The entire search plan, in the format provided by AND, can be found in Table 2 in Appendix B.

Step 3 – Appraise Each Article Using the Quality Criteria Checklists (QCC)

A QCC was completed for each included article (16 total articles). For each article included, the QCC reviewed the research purpose, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria, recruitment methods, study protocol, statistical analysis, data collection, description of data sample, summary of results, and the authors’ conclusions. In addition to this information, each QCC has relevance and validity questions that must be assessed for each included article. An example of a relevancy question is: “Would implementing the studied intervention or procedure (if found successful) result in improved outcomes for the patients/clients/population group?” An example of a validity question is: “Were intervention/therapeutic regimens/exposure factor or procedure and any comparison(s) described in detail? Were intervening factors described?” Once all of the relevancy and validity questions had been answered with a “yes,” “no,” “unclear”, or “N/A,” each article was given a rating of negative, neutral or positive. An article would receive a negative grade if most of the answers to the validity questions were “no.” An article would receive a neutral grade if the answers to the specific validity questions were “no”. An article would receive a positive grade if most of the answers to the validity questions were “yes”. It is important to point out that primary and secondary research articles have different QCCs that vary slightly.

After completing a QCC for all 16 of the included articles, 11 articles received a positive rating and 5 articles received a neutral rating. An example of a completed QCC can be found in Table 3 in Appendix B.

Step 4 – Summarize the Evidence

Once all of the included articles were reviewed using a QCC, each article was summarized using the Evidence Analysis Overview Table provided by AND. For each article, the table included author, year, study design, class, rating, study type, study purpose, intervention, and outcomes. The completed table can be found in Table 4 in Appendix B.

Step 5 – Conclusion Statement & Grade

After the PICO question was developed, the search plan was completed, the articles were reviewed using the QCCs and the articles were thoroughly summarized in the Evidence Analysis Overview Table, a conclusion statement was written and a grade was assigned to the research available on the topic of interest. The conclusion statement is: Intuitive Eating, as an intervention, and intuitive eating as a health habit have both shown to have highly positive effects on body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life in females ages 13 and older. Intuitive Eating can be successfully used to support body image acceptance; promote healthy living practices such as an increase in fruit, vegetable, and whole-grain intake as well as a decrease in foods high in fat and sugar; IE can also help alleviate disordered eating habits such as binge eating; and IE has seen to improve quality of life by decreasing the prevalence or severity of depression and allowing intuitive eaters to live a less stressful life in regards to food and body. The conclusion grade determined is: Grade Level I – Good/Strong.

The completed Conclusion Statement and Grade table provided by AND can be found in Table 6 in Appendix B.

Chapter 5. Discussion

The results of the Evidence Analysis Process demonstrated that there is more than an adequate amount of high quality research available that supports the use of Intuitive Eating for health promotion.

Effects of IE on Body Image Satisfaction

The research demonstrated that IE can have a positive impact on body image satisfaction in females 13 years and older. After undergoing a 10-week IE intervention, participants who noted an increase in their level of intuitive eating also noted an increase in body appreciation and acceptance (Bush, Rossy, Mintz, Schopp, 2015). Eating intuitively and mindfully was found to positively influence a participant’s body appreciation (Bush, Rossy, Mintz, Schopp, 2015). Integrating the principles of Intuitive Eating was found to decrease the internalization of the thinness ideal, pressure to lose weight, body shame, and body dissatisfaction (Cadena-Schlam, Lopez-Guimera, 2015). It was also found that intuitive eaters are more likely have higher levels of body appreciation, self-esteem, and overall feeling of satisfaction with themselves and their bodies (Cadena-Schlam, Lopez-Guimera, 2015). An additional 10-week IE intervention found that practicing Intuitive Eating helped participants improve self-worth and reduce negative self-talk (Cole, Horacek, 2010). The reviewed research also found that high scores on the Intuitive Eating Scale (IES) were correlated with high scores of body awareness, body responsiveness, and body satisfaction (Dittman, Freedman, 2009). Overall, the research suggested that intuitive eaters may be inherently more appreciative of their bodies and have an overall higher level of body image satisfaction than non-intuitive eaters.

Effects of IE on Healthy Living Practices

Due to the IE principle regarding unconditional permission, health professionals have exhibited concern that IE may result in excessive eating, high calorie intake and an unbalanced diet. However, the research is suggesting that intuitive eaters tend to consume less high sugar and high fat foods than restrictive eaters (Cadena-Schlam, Lopez-Guimera, 2015). IE has been associated with a more varied and nutritious diet in addition to the adoption of healthy eating patterns (Cadena-Schlam, Lopez-Guimera, 2015). Also, IE has been associated with a decrease in problematic eating behaviors such as binge-eating and emotional eating (Plateau, Papathomas, 2017). One study found that IE can help even the most extreme problematic eating behaviors that are found in patients with clinically diagnosed eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge-eating disorder, and eating disorder not otherwise specified (Richards, Crowton, Berrett, Smith, Passmore, 2017).

In addition to healthy eating practices, it was also found that IE can have a positive influence on levels of physical activity. One study found that intuitive eaters were more likely to identify with higher levels of physical activity than non-intuitive eaters. Not only this, but intuitive eaters were more likely to engage in physical activity for health issues instead of external aesthetic reasons (thinness ideals) than non-intuitive eaters. This was found to be most likely due to the fact intuitive eaters are more appreciative of their bodies and have less of a desire to change extrinsic factors than non-intuitive eaters (Dittmann, Freedmann, 2009).

Although IE is a holistic approach to health that claims a weight neutral point-of-view, research has shown that IE can also be used by health practitioners who desire patients to lose weight for health purposes. IE has been associated with a lower BMI and it has been seen that intuitive eaters are less likely to engage in weight gain behaviors (Cadena-Schlam, Lopez-Guimera, 2015). One article that studied postpartum women found that women who practiced IE were found to have a greater postpartum BMI decrease and overall weight decrease (Leahy, Berlin, Banks, Bachman, 2017). Another article reviewed the link between IE and weight loss after bariatric surgery. The study demonstrated that the higher degree of IE practiced, the greater relative BMI loss after bariatric surgery. It was found that a 1-point increase in the IES score was associated with a relative BMI loss of ~2.6% (Nogue, Molinari, Avignon, Sultan, 2019). Another study found that practicing IE was correlated with a lower BMI and that IE is a great tool for weight management, even when compared to traditional weight loss methods (Pember, 2015).

In addition to lower BMIs, a study found that IE is significantly correlated with lower levels of blood triglycerides, lower levels of total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol, higher levels of HDL cholesterol, and decreased blood pressure. Due to these factors, IE was found to be significantly correlated to a decreased risk of developing cardiovascular disease (Cadena-Schlam, Lopez-Guimera, 2015).

Effects of IE on Overall Quality of Life

According to the reviewed research, IE can have a highly positive impact on a person’s psychological well-being (Augustus-Horvath, Tylka, 2011). It was seen that IE is related to improved psychological measures and lower levels of depression (Pember, 2015). IE was also seen to be positively associated with positive effect, proactive coping, optimism and social problem solving (Cadena-Schlam, Lopez-Guimera, 2015). According to a study by Richards et al, IE had a positive influence on participants’ relationships, social role, spiritual symptoms, and attitudes. During this review, it was also found that IE can have a positive influence on people with diagnosed eating disorders as well as people exhibiting eating disorder symptoms. In a study by Bush et al, it was found that participants, in regards to disordered eating and eating disorders, in an IE intervention were 3.65 more likely to be asymptomatic than symptomatic as well as 3.65 more likely to be symptomatic than eating disordered than participants from the control group.

In summary, Intuitive Eating is a promising intervention for females 13 years or older when it comes to body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life. Further primary research is needed to test the validity of IE for health promotion, specifically long-term, randomized control trials with several follow-up periods are needed. Additionally, further research is needed regarding how to integrate IE into health care settings as well as how to introduce IE into the Nutrition Care Process (NCP) used by registered dietitians.

References

Andrew R, Tiggemann M, Clark L. Predictors and health-related outcomes of positive body image in adolescent girls: A prospective study. Developmental Psychology. 2016;52(3):463-474. doi:10.1037/dev0000095.

Anglin JC, Borchardt N, Ramos E, Mhoon K. Diet quality of adults using intuitive eating for weight loss – pilot study. Nutr Health. 2013 Jul-Oct;22(3-4):255-64. doi: 10.1177/0260106015601943.

Association for Size Diversity and Health (ASDAH). (2013). The Health at Every Size Approach. Association for Size Diversity and Health Website.https://www.sizediversityandhealth.org/index.asp

Augustus-Horvath CL, Tylka TL. The acceptance model of intuitive eating: A comparison of women in emerging adulthood, early adulthood, and middle adulthood. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2011;58(1):110-125. doi:10.1037/a0022129.

Bégin, C., Carbonneau, E., Gagnon-Girouard, M.-P., Mongeau, L., Paquette, M.-C., Turcotte, M., & Provencher, V. (2019). Eating-Related and Psychological Outcomes of Health at Every Size Intervention in Health and Social Services Centers Across the Province of Québec. American Journal of Health Promotion, 33(2), 248–258.

Bush HE, Rossy L, Mintz LB, Schopp L. Eat for Life: A Work Site Feasibility Study of a Novel Mindfulness-Based Intuitive Eating Intervention. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2014;28(6):380-388. https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy195.nclive.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s3h&AN=96935834&site=ehost-live. Accessed August 23, 2019.

Cadena-Schlam L, López-Guimerà G. Intuitive eating: an emerging approach to eating behavior. Nutricion Hospitalaria. 2015;31(3):995-1002. doi:10.3305/nh.2015.31.3.7980.

Camilleri, G. M., Méjean, C., Bellisle, F., Andreeva, V. A., Kesse-Guyot, E., Hercberg, S., & Péneau, S. (2017). Intuitive Eating Dimensions Were Differently Associated with Food Intake in the General Population-Based NutriNet-Santé Study. Journal of Nutrition, 147(1), 61–69.

Cole RE, Horacek T. Effectiveness of the “My Body Knows When” intuitive-eating pilot program. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2010;34(3):286-297. https://search-ebscohost-com.proxy195.nclive.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=105106378&site=ehost-live. Accessed August 28, 2019.

Dittmann KA, & Freedman MR. (2009). Body awareness, eating attitudes, and spiritual beliefs of women practicing yoga. Eating Disorders, 17(4), 273–292. https://doi-org.proxy195.nclive.org/10.1080/10640260902991111

Eating Disorder Hope Organization. (2020) Weight & Body Image Disorders: Causes, Symptoms, & Signs. Eating Disorder Hope Website. https://www.eatingdisorderhope.com/information/body-image.

Gast, J., Nielson, A. C., Hunt, A., & Leiker, J. J. (2015). Intuitive Eating: Associations With Physical Activity Motivation and BMI. American Journal of Health Promotion, 29(3), e91–e99.

Harrison, C. (2017, August 31). The Truth About Intentional Weight Loss. Christy Harrison Website. https://christyharrison.com/blog/the-truth-about-intentional-weight-loss.

Harrison, C. (2018, December 18). Why I’m an Anti-Diet Dietitian – and What That Really Means. Christy Harrison Website. https://christyharrison.com/blog/what-does-anti-diet-really-mean.

Harrison, C. Zavodni, K. (2019, January 28). Food Psych #183 How the Wellness Diet Harms Your Health with Katherine Zavodni.Christy Harrison Website. https://christyharrison.com/foodpsych/6/how-the-wellness-diet-harms-your-health-with-katherine-zavodni.

Leahy, K., Berlin, K., Banks, G., & Bachman, J. (2017). The Relationship Between Intuitive Eating and Postpartum Weight Loss. Maternal & Child Health Journal, 21(8), 1591–1597. https://doi-org.proxy195.nclive.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2281- 4

Loughran TJ, Harfel T, Vollmer R, Schumacher J. Effective of Intuitive Eating Intervention Through Text Messaging Among College Students. College Student Journal. 2018;52(2):232-244. https://search-ebscohost- com.proxy195.nclive.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=s3h&AN=130165003&site=ehost-live. Accessed August 23, 2019.

Nogué, M., Nogué, E., Molinari, N., Macioce, V., Avignon, A., & Sultan, A. (2019). Intuitive eating is associated with weight loss after bariatric surgery in women. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 110(1), 10–15. https://doiorg.proxy195.nclive.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqz046

Pember, S. E. (2015). Intuitive Eating Interventions for Both Disordered Eating and Weight Management. Health Education Monograph Series, 32(1), 10–14.

Plateau CR, Petrie TA, Papathomas A. Learning to eat again: Intuitive eating practices among retired female collegiate athletes. Eating Disorders. 2017;25(1):92-98. doi:10.1080/10640266.2016.1219185.

Reel, J. J., Lee, J. J., & Bellows, A. (2016). Integrating exercise and mindfulness for an emerging conceptual framework: The intuitive approach to prevention and health promotion (IAPHP). Eating Disorders, 24(1), 90–97. https://doiorg.proxy195.nclive.org/10.1080/10640266.2015.1118951

Richards PS, Crowton S, Berrett ME, Smith MH, Passmore K. Can patients with eating disorders learn to eat intuitively? A 2-year pilot study. Eating Disorders. 2017;25(2):99-113. doi:10.1080/10640266.2017.1279907.

Schnepper, R., Richard, A., Wilhelm, F. H., & Blechert, J. (2019). A combined mindfulness–prolonged chewing intervention reduces body weight, food craving, and emotional eating. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 87(1), 106– 111. https://doi-org.proxy195.nclive.org/10.1037/ccp0000361

Schoenefeld SJ, Webb JB. Self-compassion and intuitive eating in college women: Examining the contributions of distress tolerance and body image acceptance and action. Eating Behaviors. 2013;14(4):493-496. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.09.001.

Tribole E, Resch E. (2012). About Us: Meet the Original Intuitive Eating Pros. The Original Intuitive Eating Pros Website. https://www.intuitiveeating.org/about-us/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

Tribole E, Resch E. (2012). 10 Principles of Intuitive Eating. The Original Intuitive Eating Pros Website. https://www.intuitiveeating.org/10-principles-of-intuitive-eating/. Accessed August 30, 2019.

Appendix A. Approvals

CITI Training Certificate

Appendix B. Measurement Instruments

Table 1 – Completed Evidence Analysis Process PICO Question Table

The PICO Format

Specify question for evidence analysis using “PICO”

Specify Population, Intervention, Comparison, and desired Outcome.

| Population (Patient or Problem) | Intervention (cause, treatment or prognostic factor) | Comparison Intervention* (if necessary) | Outcomes | |

| Tips | Describe group (of patients). Balance precision with brevity. | What intervention are you considering? Be specific. | What is the main alternative to compare with the intervention? Be specific. | What could this intervention really affect? Be specific. |

| Identify your possible content | Females ages 13 and older | Practicing Intuitive Eating (IE) | Not practicing Intuitive Eating (IE) | Body image satisfaction Healthy living practices Quality of life |

Question for Evidence Analysis:

What is the effect of Intuitive Eating on body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life in females ages 13 and older?

*Comparison is not included in the question in order to fulfill graduate level research question requirements. Question approved by MHS program director.

Table 2 – Completed Evidence Analysis Search Plan and Results

Search Plan and Results Template

| Question: | What is the effect of Intuitive Eating on body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and overall quality of life in females ages 13 and older? |

| Date of Literature Review: | June, 2020 |

| Search Terms | Intuitive Eating, influence of Intuitive Eating, effect of Intuitive Eating, influence of Intuitive Eating on females, effect of Intuitive Eating on females, and results of Intuitive Eating |

| Inclusion Criteria: | • Age: 13 years and older • Setting: All • Health Status: All • Nutrition-Related Problem or Condition: All • Study Design: Randomized control trials, meta-analyses, narrative review and other forms of literature reviews, cohort study, cross-over study, descriptive study, cross-sectional study, longitudinal study • Size of Study Groups: >30 participants • Study Drop-Out Rate: <20% • Year Range: January 2009 – Present • Authorship: N/A • Language: English language or articles published in English • Additional Criteria: Full text articles; peer reviewed articles; gender specific data separate for ease of analysis of female participants; all races/ethnicities; contains at least 1 of 3 dependent variables (body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and quality of life) |

| Exclusion Criteria: | • Age: <13 years old • Setting: None • Health Status: None • Nutrition-Related Problems or Condition: None • Study Design: One-shot case studies, before-after study, cost benefit analysis, diagnostic/validity/reliability study, intention to treat analysis, magnitude of effect, non-controlled trial, non-randomized controlled trial, phenomena, time series, trial, trend study • Size of Study Groups: <30 participants • Study Drop-Out Rate: >20% • Year Range: Published before January 2009 • Authorship: N/A • Additional Criteria: Articles that are not full-text; articles that are not peer-reviewed; gender data aggregate only; no race/ethnicity exclusions; does not contain at least 1 of 3 dependent variables (body image satisfaction, healthy living practices, and quality of life) • Language: Not in English |

| Search Terms: Search Vocabulary | Intuitive Eating, influence of Intuitive Eating, effect of Intuitive Eating, influence of Intuitive Eating on females, effect of Intuitive Eating on females, and results of Intuitive Eating |

| Electronic Databases: | • Database: Health and Human Sciences Research Guide provided by Western Carolina University’s Hunter Library. This database includes but is not limited to Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied health (CINAHL), Cochrane Library, Medline, Psyctests, Pstcinfo, and Socindex |

| • Hits: 50 hits | |

| Inclusion List: | 1. Effectiveness of Intuitive Eating Intervention Through Text Messaging Among College StudentsEating-Related and Psychological Outcomes of HAES Intervention in Health and Social Services Centers Across the Province of Quebec 2. Intuitive eating is associated with weight loss after bariatric surgery in women. 3. The Relationship Between Intuitive Eating and Postpartum Weight Loss 4. Learning to Eat Again – Intuitive Eating Practices Among Retired Female Collegiate Athletes 5. Eat for Life: A Work Site Feasibility Study of a Novel Mindfulness-Based Intuitive Eating InterventionIntuitive Eating – 6. Associations with Physical Activity Motivation and BMI 7. Intuitive Eating Dimensions Were Differently Associated with Food Intake in the General Population-Based 8. NutriNet-Sante StudyIntegrating Exercise and Mindfulness for an Emerging Conceptual Framework – The Intuitive Approach to Prevention and Health Promotion 9. Effectiveness of My Body Knows When Intuitive Eating Pilot Program 10. Intuitive Eating Interventions for Both Disordered Eating and Weight Management. 11. The Acceptance Model of Intuitive Eating: A Comparison of Women in Emerging Adulthood, Early Adulthood, and Middle Adulthood 12. Intuitive eating: an emerging approach to eating behavior. 13. A combined mindfulness–prolonged chewing intervention reduces body weight, food craving, and emotional eating 14. Body awareness, eating attitudes, and spiritual beliefs of women practicing yoga. 15. Can patients with eating disorders learn to eat intuitively? A 2-year pilot study. 16. Body awareness, eating attitudes, and spiritual beliefs of women practicing yoga |

| List of Articles Included from Handsearch or Other Means | N/A |

| List of Excluded Articles with Reason: | 1. Intuitive Eating Scale: An Examination among Early Adolescents -Exclusion criteria: <13 years old 2. KONCEPCJE WYJAŚNIAJĄCE ZNACZENIE ŚWIADOMOŚCI ODCZUĆ CIELESNYCH W PROFILAKTYCE I TERAPII OTYŁOŚCI. -Exclusion criteria: articles not in English 3. On (Not) Knowing Where Your Food Comes From: Meat, Mothering and Ethical Eating -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 4. Reduced Taste Sensitivity in Congenital Blindness. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 5. Predictors and health-related outcomes of positive body image in adolescent girls: A prospective study. -Exclusion criteria: <13 years old 6. Coaching to improve mealtime parenting in treating pediatric obesity. -Exclusion criteria: <13 years old 7. Full of Ourselves PLUS’: Lessons learned when implementing an eating disorder and obesity prevention program. -Exclusion critera: <13 years old 8. The role of body mass index, weight change desires and depressive symptoms in the health-related quality of life of children living in urban disadvantage: Testing mediation models. -Exclusion criteria: <13 years old Pilot 9. Investigation of 2 Nondiet Approaches to Improve Weight and Health -Exclusion criteria: gender data aggregate only 10. The calorie counter-intuitive effect of restaurant menu calorie labelling. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 11. Pilot Investigation of 2 Nondiet Approaches to Improve Weight and Health (Duplicate) -Exclusion criteria: gender data aggregate only 12. Illusory Changes in Body Size Modulate Body Satisfaction in a Way That Is Related to Non-Clinical Eating Disorder Psychopathology. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 13. Experiences and Perspectives of Polycystic Kidney Disease Patients following a Diet of Reduced Osmoles, Protein, and Acid Precursors Supplemented with Water: A Qualitative Study. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 14. 社区骨质疏松患者饮食行为及健康管理策略. -Exclusion criteria: articles not in English 15. The relationship between emotions and food consumption (macronutrient) in a foodservice college setting – a preliminary study. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 16. Gut feelings: the emerging biology of gut-brain communication. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 17. Mindfulness Based Approaches to Obesity and Weight Loss Maintenance. -Discusses mindful eating not IE 18. Managing European cormorant-fisheries conflicts: problems, practicalities and policy. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 19. Theory-based explanation as intervention. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 20. Cancer Risk Factor Knowledge Among Young Adults. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 21. Dis)connected: An examination of interoception in individuals with suicidality. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 22. When commonsense does not make sense. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 23. The challenge of monitoring elusive large carnivores: An accurate and cost-effective tool to identify and sex pumas (Puma concolor) from footprints. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 24. DISAGREEMENT ABOUT TASTE AND ALETHIC SUBEROGATION. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 25. Key to the Genera of Nearctic Syrphidae. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 26. Marine mammal culling programs: review of effects on predator and prey populations. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 27. Teaching Young Children a Theory of Nutrition: Conceptual Change and the Potential for Increased Vegetable Consumption. -Exclusion criteria: <13 years old Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 28. Phylogenetic analysis reveals positive correlations between adaptations to diverse hosts in a group of pathogen-like herbivores. -Irrelevant to research question; does not discuss IE 29. Disordered eating and psychological distress among adults. -Does not discuss IE as an intervention; does not measure IE 30. Intuitive Eating – A Novel Eating Style? Evidence from a Spanish Sample -Does not discuss IE as an intervention 31. Understanding disordered eating at midlife and late life. -Irrelevant to research topic; does not discuss IE 32. The Intuitive Eating Scale-2: Item Refinement and Psychometric Evaluation with College Women and Men -Does not discuss IE as an intervention 33. Women’s experiences of changes in eating during pregnancy: A qualitative study in Dunedin, New Zealand -Irrelevant to research topic; does not discuss IE 34. Normal Weight Status in Military Service Members was Associated with Intuitive Eating Characteristic Exclusion criteria: -Does not properly split data according to sex |

| Summary of Articles Identified to Review | Number of Included Primary Research Articles Identified from all sources: 13 Number of Included Review Articles Identified from all sources: 3 Total number of included articles: 16 Total number of articles considered but excluded: 34 Total number of articles considered: 50 |

Table 3 – Example of Completed QCC

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics

Evidence Analysis Library® Worksheet Template and

Quality Criteria Checklist: Primary Research

| Citation | Richards, P. S., Crowton, S., Berrett, M. E., Smith, M. H., & Passmore, K. (2017). Can patients with eating disorders learn to eat intuitively? A 2-year pilot study. Eating Disorders, 25(2), 99–113. https://doi- org.proxy195.nclive.org/10.1080/10640266.2017.1279907 | |||||

| Study Design | 2 year pilot study | |||||

| Class | Class B | |||||

| Quality Rating | + (Positive) – (Negative) x (Neutral) | |||||

| Research Purpose | To evaluate whether it is possible to teach intuitive eating principles to inpatients with anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), and eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDON). | |||||

| Inclusion Criteria | Adult women with an eating disorder who were admitted to the in-patient treatment unit at the Center for Change during 2008-2009 | |||||

| Exclusion Criteria | Adult women without an eating disorder who were not admitted to the in-patient treatment unit at the Center for Change during 2008-2009 | |||||

| Description of Study Protocol | Recruitment: Patient admitted for in-patient treatment at the Center for Change Design: 2 year pilot study Blinding used (if applicable): N/A Intervention (if applicable): CFC’s dietary program includes a stepwise structured program that progresses from more dietary structure and intervention to less structure and intervention as patient exhibit readiness for management of dietary choices. Consultations occur every week to determine a patient’s readiness to implement this stepwise approach. Patients begin to learn about the 10 principles of Intuitive Eating soon after being admitted for treatment, but they do not receive permission to begin practicing Intuitive Eating until they exhibit a clear readiness to do so. All patient in the study initially participated in a menu where they were expected to eat 100% of their plated portions. Eventually, they transitioned to family style dining where they were able to choose menu items within guidelines and were expected to eat 100%. Only after a period of time where patients were able to demonstrate ability to plate and eat appropriately, accurately assess hunger-fullness, and resist eating disorder urges were they advanced to Intuitive Eating. Once they received approval to begin Intuitive Eating, patients were allowed to choose menu items in accordance with Intuitive Eating principles. Patients received education on the 10 Intuitive Eating principles. RDs met individually each week with the patients and discussed the Intuitive Eating principles. Weekly nutrition classes were also held where the principles were discussed and reviewed. Patients were also given opportunities to practice the principles in weekly cooking classes and during schedule meal outings. Statistical Analysis: T-tests, repeated measures analysis of variance, Cohen’s d, and Pearson correlations. | |||||

| Data Collection Summary | Timing of Measurements: 8-week program; assessments were conducted at the beginning of inpatient enrollment, transfer from inpatient to residential, and transfer from residential to discharge. Dependent Variables: eating disorder symptoms, depression, anxiety, social conflict, body image, spiritual well-being, ability to eat intuitively Independent Variables: Intuitive Eating lessons Control Variables: N/A | |||||

| Description of Actual Data Sample | Initial: 120 (0 Males 120 Females) Attrition (final N): 120 Age: M = 21.2 years old; range = 13 to 55 years old Ethnicity: 90% Caucasian; 1% African American, Asian, Hispanic Other relevant demographics: 39% AN, 30% BN, 31 EDNOS Anthropometrics: N/A Location: Center for Change | |||||

| Summary of Results | Key Findings: Collectively, patients’ scores on the outcome measures all improved significantly between the time of admission and the time of discharge. Changes on 3 of the scales (EAT, BSQ, OQ) were large and clinically significant. At the time of discharge, patients reported clinically significant improvements in eating disorder, psychological, relationship, social role, and spiritual symptoms and attitudes. Patients Intuitive Eating scorers increase significantly between the time they were admitted to the time they were discharged. Dietitians perceived that the patients’ eating behaviors become healthier during the course of treatment on all five of the behavioral dimensions they assessed (eating flexibility, comfortable eating, appropriate eating, using food to cope, obsessing about food). Other Findings: All patients with EDs were able to enhance their Intuitive Eating skills. | |||||

| Author Conclusion | The study provided preliminary evidence that Intuitive Eating behaviors and attitudes can be taught and learned in an inpatient and residential eating disorder | |||||

| treatment program. The IE principles can be effectively taught in a highly structured treatment setting. | ||||||

| Reviewer Comments | Great layout, good statistical analysis, great illustration and explanation of findings, good section of further study ideas. | |||||

| Funding Source | Center for Change | |||||

| Symbols Used | Explanation | |||||

| + | Positive – Indicates that the report has clearly addressed issues of inclusion/exclusion, bias, generalizability, and data collection and analysis | |||||

| — | Negative – Indicates that these issues have not been adequately addressed. | |||||

| x | Neutral – indicates that the report is neither exceptionally strong nor exceptionally week | |||||

| Relevance Questions | ||||||

| 1. Would implementing the studied intervention or procedure (if found successful) result in improved outcomes for the patients/clients/population group? (NA for some Epi studies) | 1 | Yes | ||||

| 2. Did the authors study an outcome (dependent variable) or topic that the patients/clients/population group would care about? | 2 | Yes | ||||

| 3. Is the focus of the intervention or procedure (independent variable) or topic of study a common issue of concern to dietetics practice? | 3 | Yes | ||||

| 4. Is the intervention or procedure feasible? (NA for some epidemiological studies) | 4 | Yes | ||||

| If the answers to all of the above relevance questions are “Yes,” the report is eligible for designation with a plus (+) on the Evidence Quality Worksheet, depending on answers to the following validity questions. | ||||||

| Validity Questions | ||||||

| Was the research question clearly stated? Was the specific intervention(s) or procedure (independent variable(s)) identified? Was the outcome(s) (dependent variable(s)) clearly indicated? Were the target population and setting specified? | 1 | Yes | ||||

| 1.1 | Yes | |||||

| 1.2 | Yes | |||||

| 1.3 | Yes | |||||

| Was the selection of study subjects/patients free from bias? Were inclusion/exclusion criteria specified (e.g., risk, point in disease progression, diagnostic or prognosis criteria), and with sufficient detail and without omitting criteria critical to the study? Were criteria applied equally to all study groups? Were health, demographics, and other characteristics of subjects described? Were the subjects/patients a representative sample of the relevant population? | 2 | Yes | ||||

| 2.1 | Yes | |||||

| 2.2 | Yes | |||||

| 2.3 | Yes | |||||

| 2.4 | Yes | |||||

| Were study groups comparable? Was the method of assigning subjects/patients to groups described and unbiased? (Method of randomization identified if RCT) Were distribution of disease status, prognostic factors, and other factors (e.g., demographics) similar across study groups at baseline? | 3 | Yes | ||||

| 3.1 | Yes | |||||

| 3.2 | Yes | |||||

| 3.3. Were concurrent controls used? (Concurrent preferred over historical controls.) 3.4. If cohort study or cross-sectional study, were groups comparable on important confounding factors and/or were preexisting differences accounted for by using appropriate adjustments in statistical analysis? 3.5. If case control study, were potential confounding factors comparable for cases and controls? (If case series or trial with subjects serving as own control, this criterion is not applicable. Criterion may not be applicable in some crosssectional studies.) 3.6. If diagnostic test, was there an independent blind comparison with an appropriate reference standard (e.g., “gold standard”)? | 3.3 | N/A | ||||

| 3.4 | Yes | |||||

| 3.5 | N/A | |||||

| 3.6 | N/A | |||||

| 4. | Was method of handling withdrawals described? 4.1. Were follow up methods described and the same for all groups? 4.2. Was the number, characteristics of withdrawals (i.e., dropouts, lost to follow up, attrition rate) and/or response rate (cross-sectional studies) described for each group? (Follow up goal for a strong study is 80%.) 4.3. Were all enrolled subjects/patients (in the original sample) accounted for? 4.4. Were reasons for withdrawals similar across groups 4.5. If diagnostic test, was decision to perform reference test not dependent on results of test under study? | 4 | Yes | |||

| 4.1 | N/A | |||||

| 4.2 | Yes | |||||

| 4.3 | Yes | |||||

| 4.4 | Yes | |||||

| 4.5 | Yes | |||||

| 5. | Was blinding used to prevent introduction of bias? 5.1. In intervention study, were subjects, clinicians/practitioners, and investigators blinded to treatment group, as appropriate? 5.2. Were data collectors blinded for outcomes assessment? (If outcome is measured using an objective test, such as a lab value, this criterion is assumed to be met.) 5.3. In cohort study or cross-sectional study, were measurements of outcomes and risk factors blinded? 5.4. In case control study, was case definition explicit and case ascertainment not influenced by exposure status? 5.5. In diagnostic study, were test results blinded to patient history and other test results? | 5 | No | |||

| 5.1 | No | |||||

| 5.2 | No | |||||

| 5.3 | No | |||||

| 5.4 | N/A | |||||

| 5.5 | N/A | |||||

| 6. | Were intervention/therapeutic regimens/exposure factor or procedure and any comparison(s) described in detail? Were intervening factors described? 6.1. In RCT or other intervention trial, were protocols described for all regimens studied? 6.2. In observational study, were interventions, study settings, and clinicians/provider described? 6.3. Was the intensity and duration of the intervention or exposure factor sufficient to produce a meaningful effect? 6.4. Was the amount of exposure and, if relevant, subject/patient compliance measured? 6.5. Were co-interventions (e.g., ancillary treatments, other therapies) described? 6.6. Were extra or unplanned treatments described? 6.7. Was the information for 6.4, 6.5, and 6.6 assessed the same way for all groups? 6.8. In diagnostic study, were details of test administration and replication sufficient? | 6 | Yes | |||

| 6.1 | N/A | |||||

| 6.2 | N/A | |||||

| 6.3 | Yes | |||||

| 6.4 | Yes | |||||

| 6.5 | Yes | |||||

| 6.6 | Yes | |||||

| 6.7 | Yes | |||||

| 6.8 | N/A | |||||

| 7. | Were outcomes clearly defined and the measurements valid and reliable? 7.1. Were primary and secondary endpoints described and relevant to the question? 7.2. Were nutrition measures appropriate to question and outcomes of concern? 7.3. Was the period of follow-up long enough for important outcome(s) to occur? | 7 | Yes | |||

| 7.1 | Yes | |||||

| 7.2 | Yes | |||||

| 7.3 | Yes | |||||